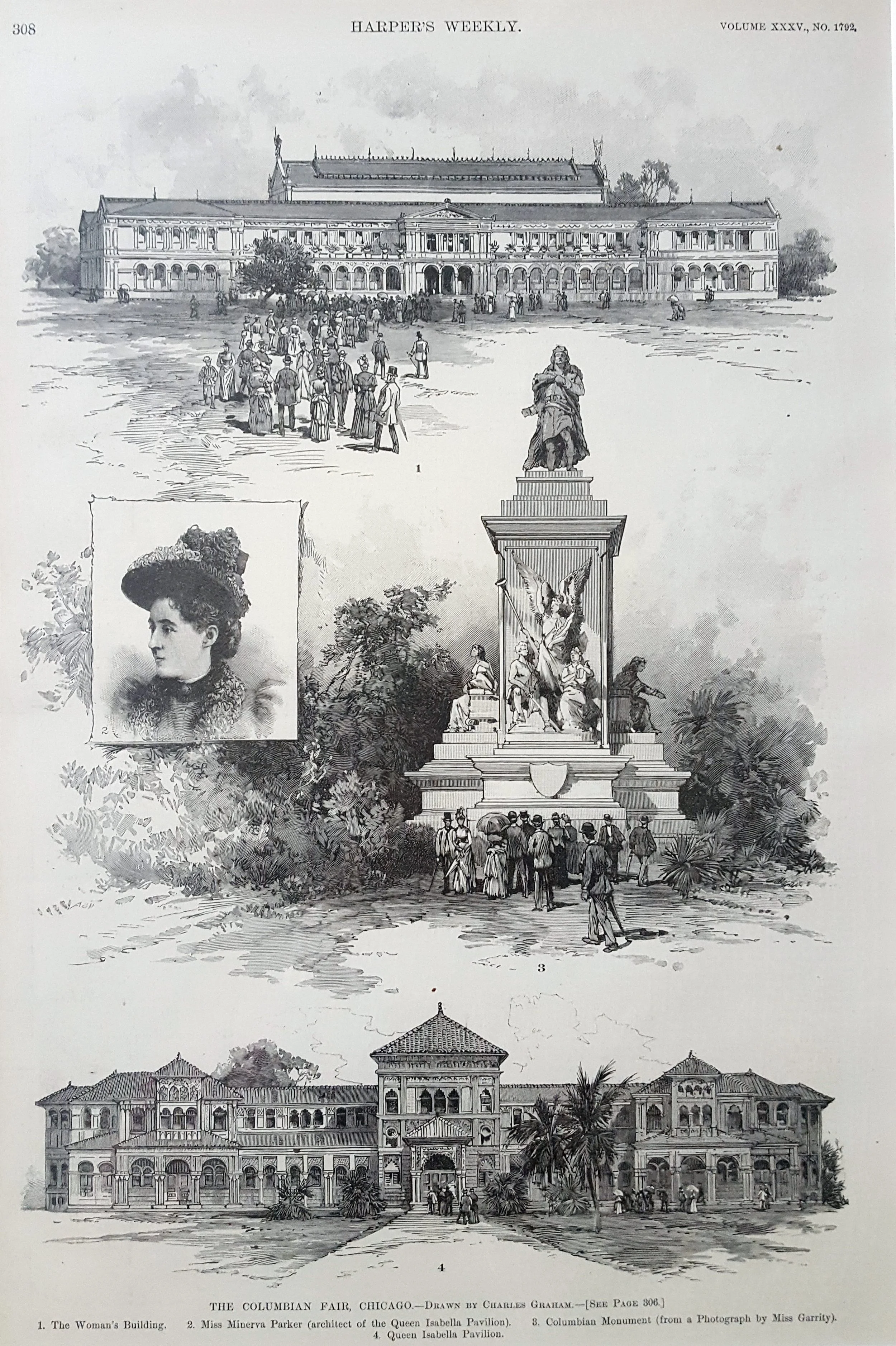

Queen Isabella Association

[World’s Columbian Exposition Fairgrounds], Chicago, IL

1890-91 | Women’s Club Pavilion | Not Built

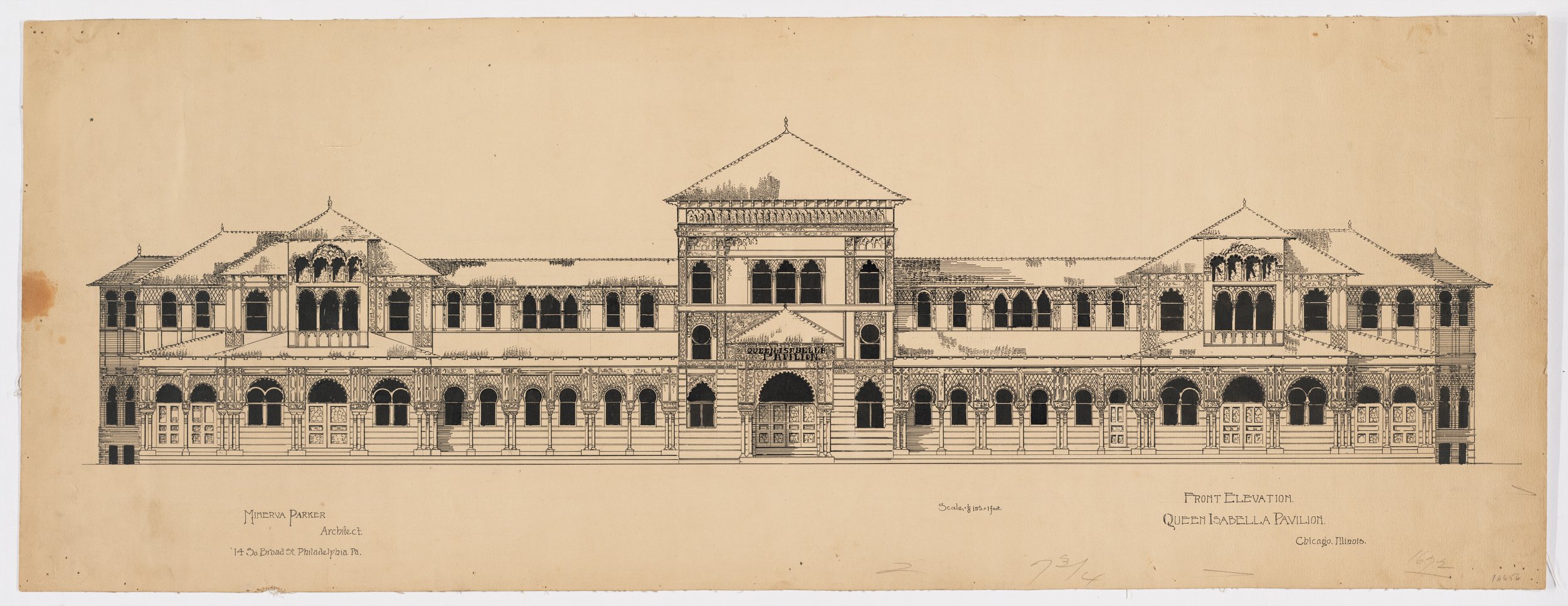

“Minerva Parker architect, 14 S. Broad street, has just been paid the distinguished compliment of receiving a letter of invitation from the Executive Committee of the Women’s Department, World’s Fair, to prepare plans for a structure to be known as the ‘Queen Isabella Pavilion,’ and to be used as a Club-house and office building, for the Committee, which consists of quite a number of leading Chicago ladies. Miss Parker will in the proposed designs confine herself entirely, to the highest type of Spanish architecture, to which she has given especial labor and study.” (August 27, 1890)

“Miss Parker has begun the drawings for the Isabella Pavilion, to be erected upon the grounds of the Exposition, at Chicago, Ill., 1893, the plans contemplate a building, two-stories high, with Spanish tile roof and the interior will be fitted with apartments for accommodation of women, care of children during a visit, a medical department, press, legal and ministers rooms, parlors for notables, musicians, stenographers, architects, designers, modistes, milliners, tailors and representatives of every trade and industry; also writing and reception rooms and an emergency department, with trained nurses and remedies at hand, as well as physicians. A sewing-room,with attendants on hand for aid in case of need, a children’s day nursery. The exact size of the structure cannot be given yet, but its main entrance will be of grand and imposing nature ornamented chiefly by a grand statue of Queen Isabella, of Spain, by the gifted sculptress, Miss Hosmer. Much must be reserved until the plans are in a better stage of development, but the outlines are sufficient to say that this work will reflect great credit upon the architect.” (November 5, 1890)

“Minerva Parker, architect, 14 S. Broad street, Phila., has completed the preliminary drawings for the ‘Isabella Pavilion,’ to be erected under her supervision at the World’s Fair, in 1892, and submitted the same to the Commissioners, that body has approved of them and commented very favorably upon their advantages and adaptation to the purposes. Miss Parker, will now proceed with the detail work.” (December 17, 1890)

“In connection with the above [the Columbian Exposition], designs will be furnished by the only woman architect in Pennsylvania, Miss Minerva Parker, 14 S. Broad street, Philada., the above plans [the Woman’s Building] are in no way connected with the Isabella Pavilion, which will be designed and constructed under the supervision of the above named architect.” (February 11, 1891)

“The committee in charge of erection of the ‘Isabella Pavilion,’ at the Columbian Exposition, to be held at Chicago, Ill., 1893, is at present considering the feasibility of erecting a permanent, instead of a temporary structure, which will cost about $250,000, and if concluded upon the architect for the Isabella Pavilion, Minerva Parker, 14 S. Broad street, Phila., will also prepare the plans and supervise the construction.” (March 11, 1891)

“While Miss Parker makes the planning of beautiful homes a specialty, those of a more public character have not been neglect. Among these are the plans for the Isabella Pavilion at the World’s Fair, Chicago.” (November 4, 1891)

—

The Queen Isabella Association was a proto-feminist organization established in tribute to Queen Isabella of Spain. The women of the club, who called themselves “Isabellas,” insisted that the queen deserved equal credit for Christopher Columbus’ voyage to the Americas, and they raised funds for a pavilion and statue to be erected in her honor at the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago. They hired Minerva (apparently without any competition), and Minerva modeled her design after the Alhambra Palace in Spain. She received extensive press for the project in newspapers and magazines around the country.

As a result of fair politicking, however, her pavilion was never built. Instead, the Board of Lady Managers pushed the Queen Isabella Association off-grounds, so that their Woman’s Building would be the sole focus of women and architecture at the fair. Despite the circumstances that cost her the commission for the Isabellas, Minerva was quite supportive of Sophia Hayden, the architect of the Woman’s Building. When Sophia withdrew from the project due to stress, Minerva came to her defense (and the defense of all women architects) in an essay for American Architect and Building News.